Simon Ivarsson

Well-known member

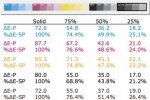

Can someone explain in simple words why 50% should print as 68%

I understand that back in the days dot gain was unavoidable due to the manual process.

I'm just guessing now, but the only way it was possible to compensate for dot gain was with the ink and printing press it self.

What I don't understand is why we today still aims for a target that is not linear.

With digital prepress and CTP its not impossible to print linear anymore.

in the manual for eskos IntelliCurve they explain it like this..

"The reason for this is that the human eye expects to see some dot gain, because people are used to look at a certain amount of dot gain, which has historically grown. People have learnt to get used to a standard offset dot gain (50% prints as 68.5%), a print result with dot gain that has always been considered as OK.”

And that just makes me more confused..

Because during press check I compare the original photo with the printed result. And they should defiantly match.

I surtenly don't want the mid tones to be 20 darker.

I understand that back in the days dot gain was unavoidable due to the manual process.

I'm just guessing now, but the only way it was possible to compensate for dot gain was with the ink and printing press it self.

What I don't understand is why we today still aims for a target that is not linear.

With digital prepress and CTP its not impossible to print linear anymore.

in the manual for eskos IntelliCurve they explain it like this..

"The reason for this is that the human eye expects to see some dot gain, because people are used to look at a certain amount of dot gain, which has historically grown. People have learnt to get used to a standard offset dot gain (50% prints as 68.5%), a print result with dot gain that has always been considered as OK.”

And that just makes me more confused..

Because during press check I compare the original photo with the printed result. And they should defiantly match.

I surtenly don't want the mid tones to be 20 darker.